Before his name became synonymous with salad dressings, Paul Newman was one of the world’s greatest movie stars. In 1966, Newman brought to the silver screen the private eye Lew Harper in Harper, based on the novel The Moving Target by Ross Macdonald. Fans of Macdonald’s detective novels (myself included) recognize that Newman’s Harper differs greatly from Macdonald’s. The most conspicuous alteration being the detective’s surname.

In Macdonald’s work, Lew’s last name was Archer, which the Canadian-born author chose as both a reference to his own astrological sign (Sagittarius the archer) and as obeisance to Sam Spade’s doomed partner, Miles Archer, in The Maltese Falcon. So what caused the seemingly arbitrary name change? It depends on whom you ask, but most likely it boils down to money and superstition.

To fans of the hardboiled detective genre, Macdonald ranks among the Holy Trinity of authors, alongside Dashiell Hammett (The Maltese Falcon) and Raymond Chandler (The Big Sleep). Hammett essentially invented the form, Chandler furthered and refined it, and Macdonald elevated it. By introducing psychological realism, Freudian analysis, and philosophy to the mystery story, Macdonald is revered, even in academic circles, for applying traditional literary techniques to an often meretricious form.

Screenwriter and novelist William Goldman, best remembered for The Princess Bride, brought Macdonald’s work to the attention of movie producer Elliot Kastner, who wanted to make a movie with “some balls”. Goldman wrote the adaptation of The Moving Target, the first Lew Archer novel, which he initially titled Archer. Paul Newman, hot from successes like Cat on a Hot Tin Roof (1958) and Sweet Bird of Youth (1962), was chosen to play the empathetic gumshoe.

According to Goldman, Newman had good luck with The Hustler (1961) and Hud (1963), and hoped another film with an “H” title would continue the trend. Goldman happily acquiesced his star’s superstitions, settling on Harper. “So we needed a different name,” Goldman wrote years later. “Harper seemed OK, the guy harps on things, it’s essentially what he does for a living.” According to other accounts, the name change came from producers, who only owned the movie rights to The Moving Target, not the other Archer books.

In Harper, Lauren Bacall plays a wealthy woman who hires Harper to find her missing husband. Bacall’s presence deliberately homages her iconic performance as femme fatale Vivian Sternwood in The Big Sleep (1946). Despite positive critical reception and success at the box-office, a sequel to Harper toiled away in development hell for a number of years. Originally, Goldman wrote a follow-up based on the eleventh Lew Archer book, The Chill. That screenplay remains unproduced.

Nearly a decade later, Newman as Harper finally returned to the screen in The Drowning Pool (1975), based on the second Lew Archer book. In this film, Harper helps a former girlfriend (played by Newman’s actual wife, Joanne Woodward) thwart a blackmailing attempt. Woodward suggested relocating the setting from Southern California to Louisiana, a choice considered heretical by most Macdonald purists. Part of Macdonald’s writing genius was his ability to create a sense of place. Santa Teresa, a fictionalized name for Santa Barbara, and the surrounding suburbs are so intrinsic to Archer’s character and Macdonald’s themes. That said, those unfamiliar with Macdonald’s work won’t sense the reverberations this relocation has on the narrative.

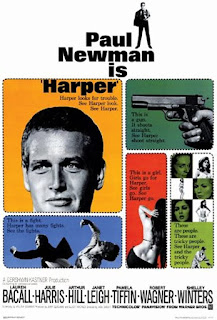

Harper and The Drowning Pool are radically different from each other, both epitomizing the era of filmmaking in which they were manufactured. Harper oozes and reeks of 60s carefree nonchalance, complete with bikini glad women and their poolside gyrations. Harper treats its mystery with a sly smirk. The tonal atmospherics are jazzy, illuminated with psychedelic oranges and yellows. Harper feels more akin to the Dean Martin Matt Helm films (1966-1969) than anything reminiscent of Bogart, Hammett, Chandler, or Macdonald.

The Drowning Pool arrived midway through the moody and broody 70s. A dour, world-weary and mournful aura permeates the film, more akin to The French Connection (1971) and Serpico (1972). The violence and the mystery lack Harper’s insouciant charms, shedding the nonchalance for paranoia. The Drowning Pool came out the same year as another post-Watergate P.I. movie, Night Moves (1975). Both films reflect the national anxiety of the time. Interestingly, both The Drowning Pool and Night Moves feature a teenaged Melanie Griffith, playing almost the same character.

The Drowning Pool’s screenplay is credited Tracy Keenan Wynn, Lorenzo Semple Jr., and Walter Hill, though none of them seem particularly proud or pleased with the final film, a sentiment shared by critics and audiences. The Drowning Pool failed to match or surpass the success of Harper. However, I am probably the one person on Earth to prefer The Drowning Pool. Neither film really captures the brilliance and ingenuity of Macdonald’s work, but The Drowning Pool, despite the bone-headed move to set it in Louisiana, comes closer than Harper. Though both films are currently available to stream, you should seek out Ross Macdonald’s novels first. When it comes to Lew Archer (or Harper), even Paul Newman’s terrific acting pales in comparison to Macdonald’s hardboiled prose.

-T.Z.